Hadas Kotek » Blog »

Stereotypical Gender Effects in 2016

May 18, 2023

I’ve been thinking recently about a project that I was involved in in 2016, which I continue to refer back to once in a while because it is the most striking replication study I’ve ever participated in. My collaborators on this study were Dr. Meg Grant, Jayun Bae (who was then a linguistics major at the McGill University Department of Linguistics), and Dr. Jeff Lamontagne (who was then a graduate student at McGill Linguistics1). We never published these results beyond a conference presentation2 because Reasons3 but I think it’s as relevant now as it’s ever been.

The original study

We were interested in replicating Kennison and Trofe (2003).4 The K&T study had two components: (a) a norming study in which participants rated 405 nouns on a 7-point scale ranging from “stereotypically female” to “stereotypically male”, (b) a reading study consisting of sentences using some of the most stereotypically skewed nouns and a pronoun that either matched or mismatched expectations. An example sentence from the study looks like this (the study contained 32 sentence paradigms):

The {executive/secretary} distributed an urgent memo.

{He/She} made it clear that work would continue as normal.

In the norming study, “executive” was rated as stereotypically male (average score 5/7) and “secretary” was rated as stereotypically female (average score 1.83/7).

The study found surprisal effects for mismatched noun/pronoun pairs in the form of a slowdown in reading times at the point of encountering the pronoun. That is, reading times were greater at the point of reading the pronoun “she” when it followed the noun “executive” and likewise for “he” when it followed the noun “secretary”.

These results suggest that gender stereotypes can influence co-reference resolution in pronouns. This has societal implications and also practical implications for researchers whose studies use these kinds of nouns and pronouns, so they should control for these effects to avoid spurious interference with their measures of interest. There were some additional parts to the discussion, and one can generally wonder how good this occupation-based probe really is as a proxy for measuring gender bias in the general case, but I’ll leave these topics open here.

The replication study

We were interested in replicating the K&T study, since it had been close to 15 years since the original data had been collected. We were further interested in correlating the results with other parts of the participants’ identity, including age and gender. We also added some newer nouns to the norming study, such as “blogger” and “internet celebrity”, which weren’t included in the original study. In total, our list contained 472 nouns.

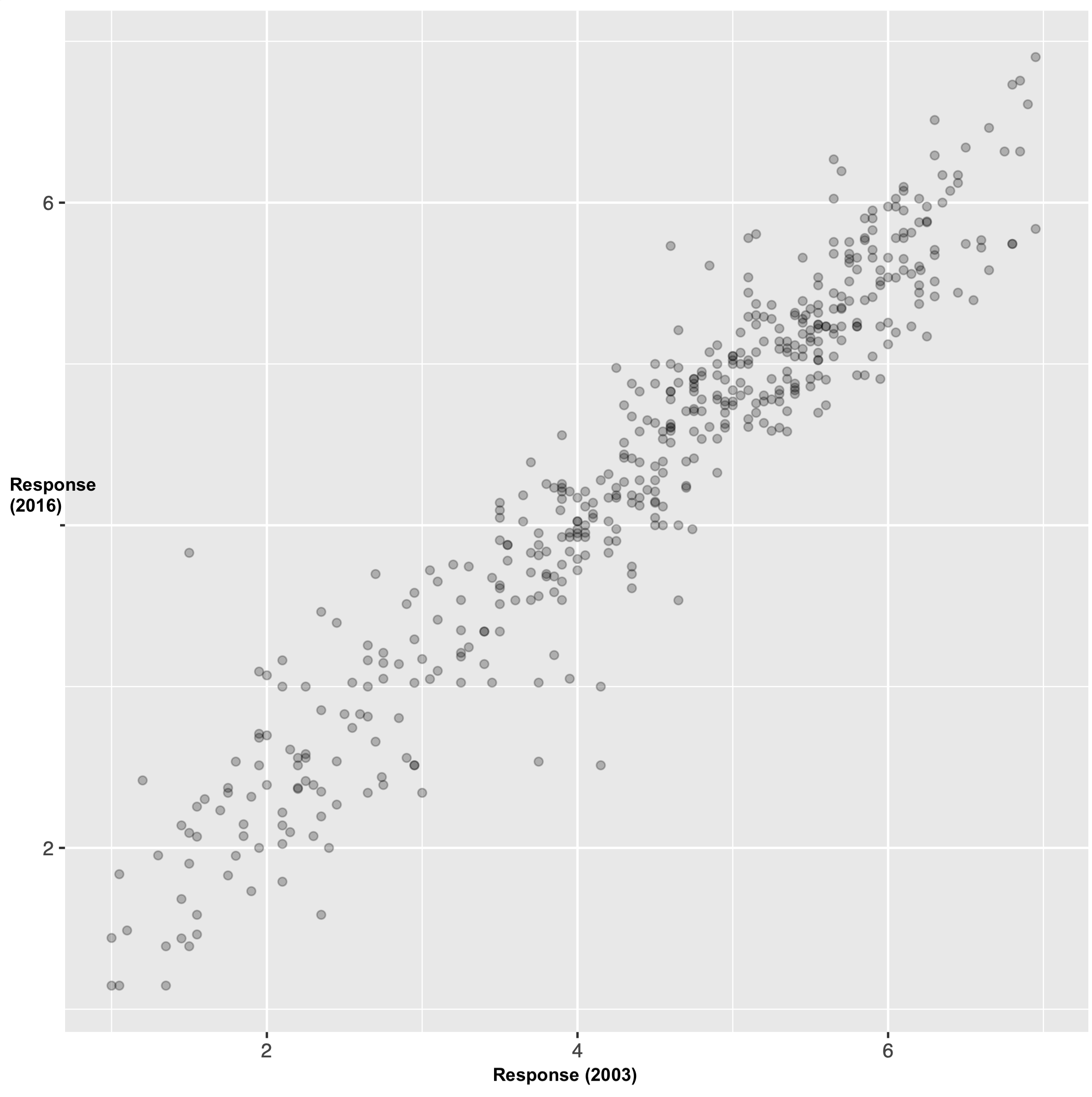

We completed the norming phase of the study. 86 participants (42 female, age range 19-70) rated the nouns on a scale from 1 (Mostly male) to 7 (Mostly female). The scale was reversed for half of participants. Participants were recruited online using Amazon Mechanical Turk, and they were paid for their participation. Overall, the correlation between our ratings and those collected by K&T was strikingly strong (r(393) = .96, p < .001).

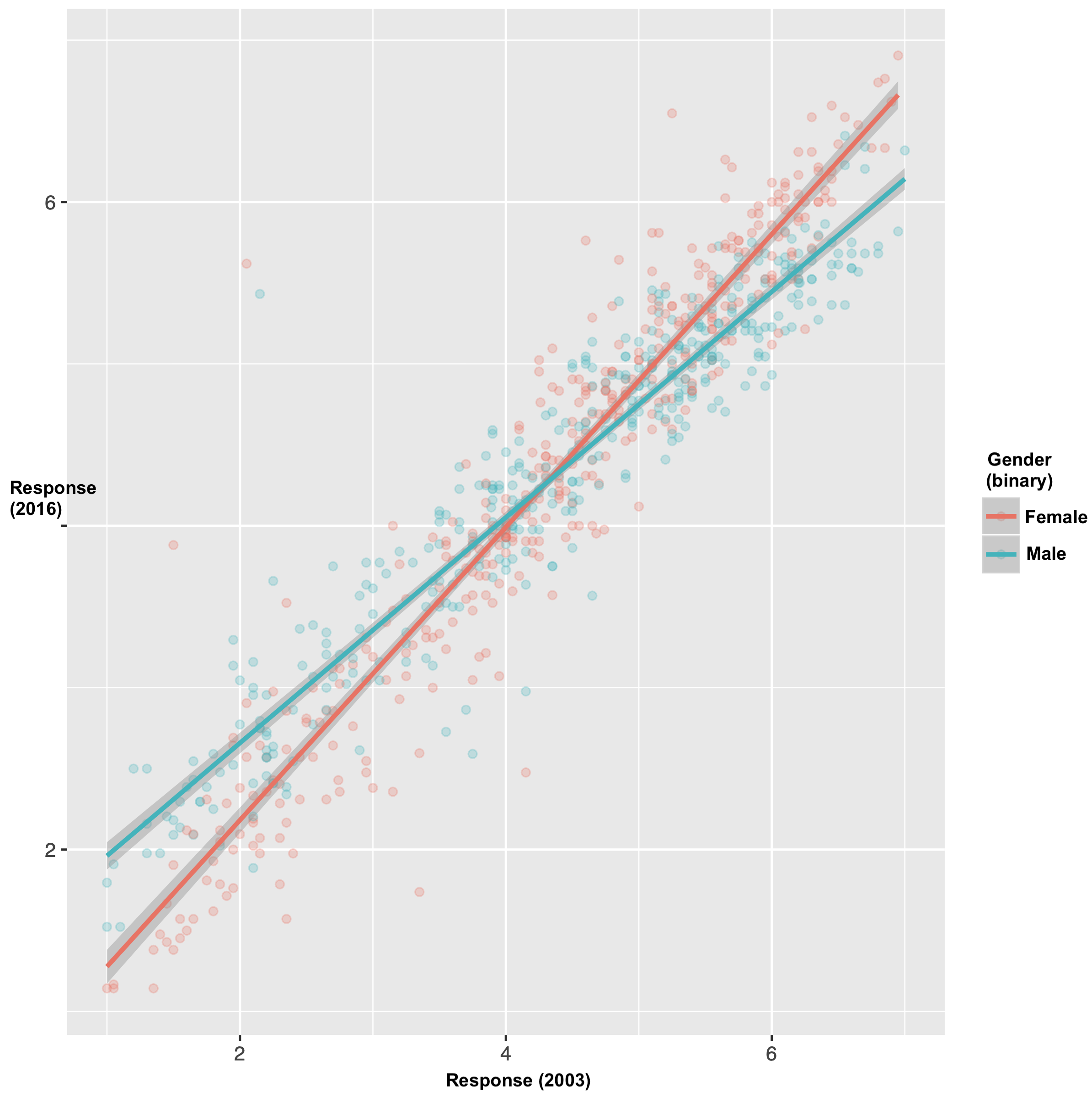

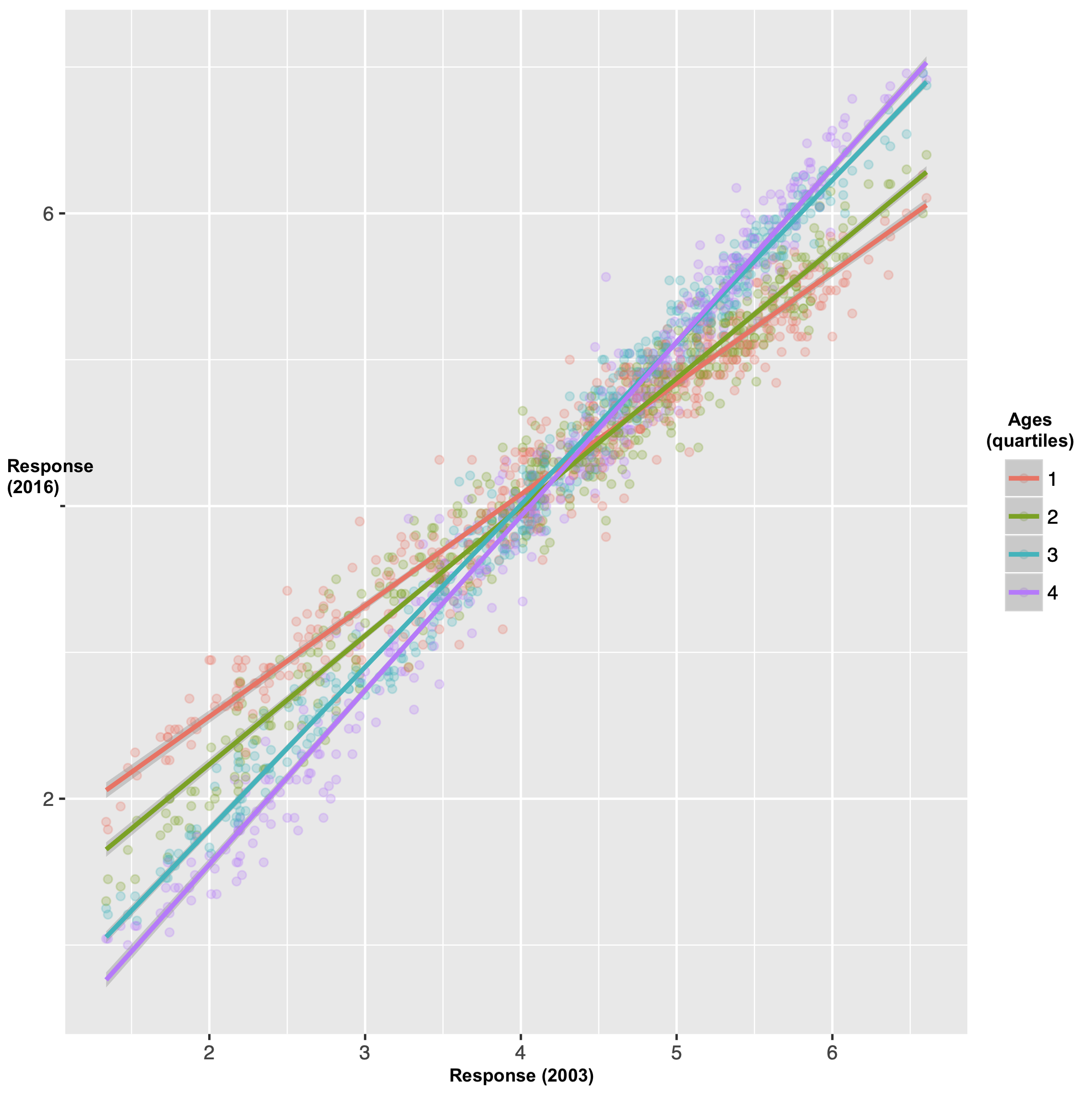

We can also compare the results by gender (using a binary female/male classification) and age (using bins by quartile5). In the by-gender plot, we can observe that there was a better correlation between the 2003 and 2016 ratings for the women, whereas the men seem to be on the whole using the extreme points of the scale less frequently, such that they rated the “stereotypically female” nouns as less stereotypically female than in 2003 and likewise for the “stereotypically male” nouns. We observe a similar effect by age: When broken down by age group, the oldest age group maps most closely to the original ratings and the youngest age group shows what I might call the strongest debiasing effect in the sense of using the extreme points on the scale less frequently.

On the whole I take this to be an encouraging effect. But still, it’s so minor when viewed on the whole, that I don’t know how much we can make of it.

What we didn’t get to

We never completed the Self-Paced Reading portion of the study. And we never collected enough data to report on correlations with self-reported political beliefs on gender and sexuality, which we were originally interested in including in the study. As a result, I am not reporting on those findings here.

Long story short, Meg and I both took other jobs within a few months of starting this study, we both moved to different countries, and we simply lost our funding to support this project. It’s a common story of academic precarity. For me, really, this was the last experimental study I was able to do in my academic career, and already at that point my lack of access to lab resources meant that I was no longer competitive for experimental linguistics jobs. I really enjoyed doing experimental work as part of my PhD program (and I think it’s one of the most useful skills I learned that I use now in my non-academic job!), so it was a shame but it was hard to see how to change it.

Given all these difficulties, we never published a paper based on these findings. At the time we thought that just replicating the norming part wasn’t enough. Maybe that was true, though I’ve always thought at least it could have been a proceedings paper. Regardless, I think that these results continue to be as relevant now as ever, and the fact that the correlation was so strong really says something about us as a society. So, here it is now, at least in a blog post form.

The dataset

The full results are available here (as a csv file). The file contains ~400 nouns that were rated in K&T (2003) and replicated by us, and an additional ~70 which we added to our study. Ratings are calibrated so 1=’stereotypically female’ and 7=’stereotypically male’ as in the reported data in K&T. Data is reported by gender and in the aggregate, alongside the ratings from K&T where available. We also include standard deviation, as in K&T.

Epilogue: gender is not a binary!

Whenever I do a gender study, I want to scream off the roof tops that we are making a simplifying assumption of a gender binary which is Definitely Positively Inaccurate. We’re also ignoring how any of the results might be different for trans people, again an important aspect. It’s so hard to avoid these simplifications, especially when we want to compare our results with older studies which didn’t collect this data or with official statistics such as from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics which likewise doesn’t report on anything beyond the binary. One day I’ll go back and redo everything the way I really want it to. For now, I want to end this post by explicitly noting the assumption and its potential harms.

Disclaimer: none of my co-authors are responsible for anything that I have written here, including of course my interpretation of the results. But the results are a part of a collaborative project, so if you want to cite them, please cite the conference presentation (see note 2 immediately below), so my co-authors can get the credit they deserve.

Notes

-

A fun aside! I ran into Jeff at the LSA in January 2023 and he introduced me to his student. It hasn’t yet ceased to blow my mind when former students introduce me to their current students. It’s an amazing feeling! ↩

-

Grant, Margaret, Hadas Kotek, Jayun Bae and Jeffrey Lamontagne. Stereotypical Gender Effects in 2016. CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing 30, MIT, April 2017. ↩

-

In one word: precarity. In two: money and precarity. (Or is that three?) ↩

-

Kennison, S. M., & Trofe, J. L. (2003). Comprehending Pronouns: A Role for Word-Specific Gender Stereotype Information. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 32(3), 355–378. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023599719948 ↩

-

Specifically: bin1 = 19-30, bin2 = 31-39, bin3= 40-51, bin 4= 52-70 ↩